Having made our way through the first seven chapters of this text, we’re now well aware that a network consists of many complex, interacting pieces of hardware and software – from the links, bridges, routers, hosts and other devices that comprise the physical components of the network to the many protocols (in both hardware and software) that control and coordinate these devices. When hundreds or thousands of such components are cobbled together by an organization to form a network, it is not surprising that components will occasionally malfunction, that network elements will be misconfigured, that network resources will be overutilized, or that network components will simply “break” (e.g., a cable will be cut, a can of soda will be spilled on top of router). The network administrator, whose job it is to keep the network “up and running,” must be able to respond to (and better yet, avoid) such mishaps. With potentially thousands of network components spread out over a wide area, the network administrator in a network operations center (NOC) clearly needs tools to help monitor, manage, and control the network. In this chapter, we’ll examine the architecture, protocols, and information base used by a network administrator in this task.

Before diving in to network management itself, let’s first consider a few illustrative “real-world” non-networking scenarios in which a complex system with many interacting components must monitored, managed, and controlled by an administrator. Electrical power-generation plants (at least as portrayed in the popular media, e.g., movies such as the China Syndrome) have a control room where dials, gauges, and lights monitor the status (temperature, pressure, flow) of remote valves, pipes, vessels, and other plant components. These devices allow the operator to monitor the plant’s many components, and may alert the operator (the famous flashing red warning light) when trouble is imminent. Actions are taken by the plant operator to control these components. Similarly, an airplane cockpit is instrumented to allow a pilot to monitor and control the many components that make up an airplane. In these two examples, the “administrator” monitors remote devices and analyzes their data to ensure that they are operational and operating within prescribed limits (e.g., that a core meltdown of a nuclear power plant is not imminent, or that the plane is not about to run out of fuel), reactively controls the system by making adjustments in response the changes within the system or its environment, and proactively manages the system, e.g., by detecting trends or anomalous behavior that allows action to be taken before serious problems arise. In a similar sense, the network administrator will actively monitor, manage and control the system with which s/he is entrusted.

In the early days of networking, when computer networks were research artifacts rather than a critical infrastructure used by millions of people a day, “network management” was an unheard of thing. If one encountered a network problem, one might run a few pings to locate the source of the problem and then modify system settings, reboot hardware or software, or call a remote colleague to do so. (A very readable discussion of the first major “crash” of the ARPAnet on October 27, 1980, long before network management tools were available, and the efforts taken to recover from and understand the crash is [RFC 789]). As the public Internet and private intranets have grown from small networks into a large global infrastructure, the need to more systematically manage the huge number of hardware and software components within these networks has grown more important as well.

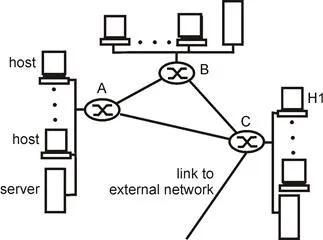

Figure 8.1-1: A simple scenario illustrating the uses of network management

In order to motivate our study of network management, let’s begin with a simple example. Figure 8.1-1 illustrates a small network consisting of three routers, and a number of hosts and servers. Even in such a simple network, there are many scenarios in which a network administrator might benefit tremendously from having appropriate network management tools:

- Failure of an interface card at a host (e.g., H1) or a router (e.g., A). With appropriate network management tools, a network entity (e.g. router A) may report to the network administrator that one of its interfaces has gone down (which is certainly preferable than a phone call to the NOC from an irate user who says the network connection is down). A network administrator who actively monitors and analyzes network traffic may be able to really impress the would-be irate user by actually detecting problems in the interface ahead of time and replacing the interface card before it fails. This could be done, for example, if the administrator noted an increase in checksum errors in frames being sent by the soon-to-die interface.

- Monitoring traffic to aid in resource deployment. A network administrator might monitor source-to-destination traffic patterns and notice, for example, that by switching servers between LAN segments, the amount of traffic that crosses multiple LANs could be significantly decreased. Imagine the happiness all around (especially in higher administration) when better performance is achieved with no new equipment costs. Similarly, by monitoring link utilization, a network administrator might determine that a LAN segment, or the external link to the outside world is overloaded and a higher-bandwidth link should thus be provisioned (alas, at an increased cost). The network administrator might also want to be notified automatically when congestion levels on a link exceed a given threshold value in order to address a provisioning problem before it becomes serious.

- Detecting rapid changes in routing tables. Route flapping – frequent changes in the routing tables – may indicate instabilities in the routing or a misconfigured router. Certainly, the network administrator who has improperly configured a router would prefer to discover the error his/herself, before the network goes down.

- Monitoring for SLAs. With the advent of Service Level Agreements (SLA) – contracts that define specific performance metrics and acceptable levels of network provider performance with respect to these metrics – interest in traffic monitoring has increased significantly over the past few years [Larsen 1997]. UUnet and AT&T are just two of many many network providers that guarantee SLAs [UUNet 1999, AT&T 1998] to their customers. These SLAs include service availability (outage), latency, throughput and outage notification requirements. Clearly, if performance criteria are to be part of a service agreement between a network provider and its users, then measuring and managing performance will be of great importance to the network administrator.

- Intrusion detection. A network administrator may want to be notified when network traffic arrives from, or is destined to, a suspicious source (e.g., host or port number). Similarly, a network administrator may want to detect (and in many cases filter) the existence of certain types of traffic (e.g., source-routed packets, or a large number of SYN packets directed to a given host) that are known to be characteristic of certain attacks.

The ISO, the organization that gave us the well-known 7-layer ISO reference model (see Chapter 1), has also created a network management model, that is useful for placing the above anecdotal scenarios in a more structured framework. Five areas of network management are defined:

- Performance management. The goal of performance management is to quantify, measure, report, analyze and control the performance (e.g., utilization, throughput) of different network components. These components include individual devices (e.g., links, routers, and hosts) as well as end-end abstractions such as a path through the network. We will see shortly that protocol standards such as the Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) [RFC 2570] play a central role in performance management.

- Fault management. The goal of fault management is to log, detect, and respond to fault conditions in the network. The line between fault management and performance management is rather blurred. We can think of fault management as the immediate handling of transient network failures (e.g., link, host or router hardware or software outages), while performance management takes the longer term view of providing acceptable levels of performance in the face of varying traffic demands and (hopefully rare) network device failures. As with performance management, the SNMP protocol plays a central role in fault management of IP networks.

- Configuration management. Configuration management allows a network manager to track which devices are on the managed network and the hardware and software configurations of these devices.

- Accounting management. Accounting management allows the network manager to specify, log, and control user and device access to network resources. Usage quotas, usage-based charging, and the allocation of resource access privileges all fall under accounting management.

- Security management. The goal of security management is to control access to network resources according to some well-defined policy. The key distribution centers and certificate authorities that we studied in section 7.4 are components of security management. The use of firewalls to monitor and control external access points to one’s network, a topic we will study in section 8.4, is another crucial component.

In this chapter, we’ll cover only the rudiments of network management. Our focus will be purposefully narrow – we’ll examine only the infrastructure for network management – the overall architecture, network management protocols, and information base through which a network administrator “keeps the network up and running.” We’ll not cover the decision making processes of the network administrator, who must plan, analyze, and respond to the management information that is conveyed to the NOC. In this area, topics such as fault identification and management [Katzela 1995, Mehdi 1997], proactive anomaly detection [Thottan 1998], alarm correlation [Jakobson 1993], and more come into consideration. Nor will we cover the broader topic of service management [Saydam 1996] – the provisioning of resources such as bandwidth, server capacity and the other computational/communication resources needed to meet the mission-specific service requirements of an enterprise. In this latter area, standards such as TMN [Glitho 1995, Sidor 98] and TINA [Hamada 1997] are larger, more encompassing (and arguably much more cumbersome) standards that address this larger issue. TINA, for example, is described as “a set of common goals, principles, and concepts cover the management of services, resources, and parts of the Distributed Processing Environment” [Hamada 1997]. Clearly, all of these topics are enough for a separate text, and would take us a bit far afield from the more technical aspects of computer networking. So, as noted above, our more modest goal here will be cover the important “nuts and bolts” of the infrastructure through which the network administrator keeps the bits flowing smoothly

An often-asked question is “What is network management?” Our discussion above has motivated the need for, and illustrated a few of the uses of, network management. We’ll conclude this section with a single-sentence (albeit a rather long, run-on sentence) definition of network management from [Saydam 1996]:

“Network management includes the deployment, integration and coordination of the hardware, software and human elements to monitor, test, poll, configure, analyze, evaluate and control the network and element resources to meet the real-time, operational performance, and Quality of Service requirements at a reasonable cost.”

It’s a mouthful, but it’s a good workable definition. In the following sections, we’ll add some meat to this rather bare-bones definition of network management.